Space Archaeology – Help Find Ancient Sites from Home

About This Project

Help Find Ancient Egyptian Sites on your Coffee Break

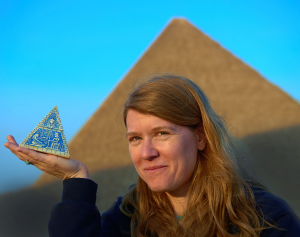

Sarah Parcak is a professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and she’s a space archaeologist. Her new book is called “Archaeology from Space.”

Parcak was a child of the 80’s and one of her favorite movies was, Raiders of the Lost Ark. It made a big impact on her. She “fell in love with the idea of archaeology and discovery.” Also while growing up, Sarah spent a lot of time with her grandfather, Harold Young, who was a forestry professor at the University of Maine, and was one of the pioneers in using aerial photographs for identifying and measuring areas of forest.

Combining her love of Egyptology with the technology of remote sensing, Sarah became a space archaeologist. She uses satellite imagery taken from space to map and model ancient landscapes here on earth.

Combining her love of Egyptology with the technology of remote sensing, Sarah became a space archaeologist. She uses satellite imagery taken from space to map and model ancient landscapes here on earth.

“Everything on the surface of the planet has its own chemical signature. Think of think of how each person writes their name. Everybody writes their name differently. Well the same thing kind of applies to everything on the earth’s surface or whether you’re sand or soil or a type of vegetation you’re going to look a little bit different.”

Sarah runs images of ancient sites taken of earth through computer algorithms that analyze parts of the light spectrum that we can’t see with our human eyes. For instance, plants growing on top of a stone wall have a different chemical register than those growing in soil. This makes it possible to find stone walls and roads.

“Think of it like a like a space based X-Ray, where you’re seeing things that are otherwise invisible or hidden to us on the ground. So then once you’ve identified this very specific chemical signature of an archaeological site you then apply these techniques and algorithms that make other features pop out as well.”

Sarah used this technique to discover some incredible ancient sites in Peru, Nova scotia and Egypt, including the Lost City of Tanis from Raiders of the Lost Ark.

“Tanis was Egypt’s capital, about 3000 years ago. So, think King Tut. Lots of gold,

A satellite image of the archaeological site of Tanis, after processing. Sarah Parcak used satellite data to find the ancient Egyptian city.

lots of imperialism, lots of foreign expeditions, it’s an incredibly wealthy time. It was Egypt’s capital for 400 years. It’s hard for us in the U.S. to get our head around it, because we as a nation are not 400 years old. Tanis is a massive massive city. There would have been tens of thousands of people that would have lived there. There would have been palaces and large administrative complexes. This would have been think of like a combined. Washington D.C. L.A. New York all rolled into one.”

Sarah says she loves archaeology because it gives her insights on what it means to be human. She uses her technology not only to uncover the past stories of humanity – but also to save it.

“So many sites around the world are getting destroyed not just by ISIL, but by urbanization by deforestation by the rising waters due to climate change. So if we don’t map these sites quickly and get a sense of what’s there how can we even know what to protect. If you get a map at first and then you need to triage and decide what to save.

Sarah decided in order to save all the archaeological sites on the planet, she was going to need help. A lot of help. so she set up an organization called Global Explorer https://www.globalxplorer.org/, which allows anyone in the world to look at satellite imagery and help map and find ancient ruins.

“GlobalXplorer has over eighty-six-thousand participants, from nearly every country in the world. The crowd has found close to 20 thousand potential archaeological sites. We collaborated with a team of archaeologists that took data that the crowd found in the Nazca region and it helped them to find over 50 new Nazca lines, those beautiful animals and shapes and figures that are carved into the landscape.

“GlobalXplorer has over eighty-six-thousand participants, from nearly every country in the world. The crowd has found close to 20 thousand potential archaeological sites. We collaborated with a team of archaeologists that took data that the crowd found in the Nazca region and it helped them to find over 50 new Nazca lines, those beautiful animals and shapes and figures that are carved into the landscape.

One of Sarah’s favorite Citizen Scientists is Doris Jones.

“Doris is 92-years-old. She is disabled and lives in Cleveland Ohio. Doris ended up being one of our super users, she’s looked at tens of thousands of archaeological tiles. She’s this bright spark in the universe. And when we talk to her about using the platform she said she felt part of this much bigger community, in spite of the fact that she has difficulty leaving home. So to me when I learned that Doris and others like her were using the platform, I felt you know we’ve done something right.”

With the help of Doris Jones and other citizen scientists, Sarah Parcak hopes to map the entire planet in ten years.

“I think we are in this race against time. Archaeologists can’t do it by themselves. You know so many government ministries around the world are struggling with funding and support. So we need the eyes of the world on these sites to help empower archaeologists and heritage people and governments to do their jobs better. And that’s why I wrote the book I wanted people to understand why what the past can teach us so that maybe we better shot it at existing or at least doing a better job of existing today.”