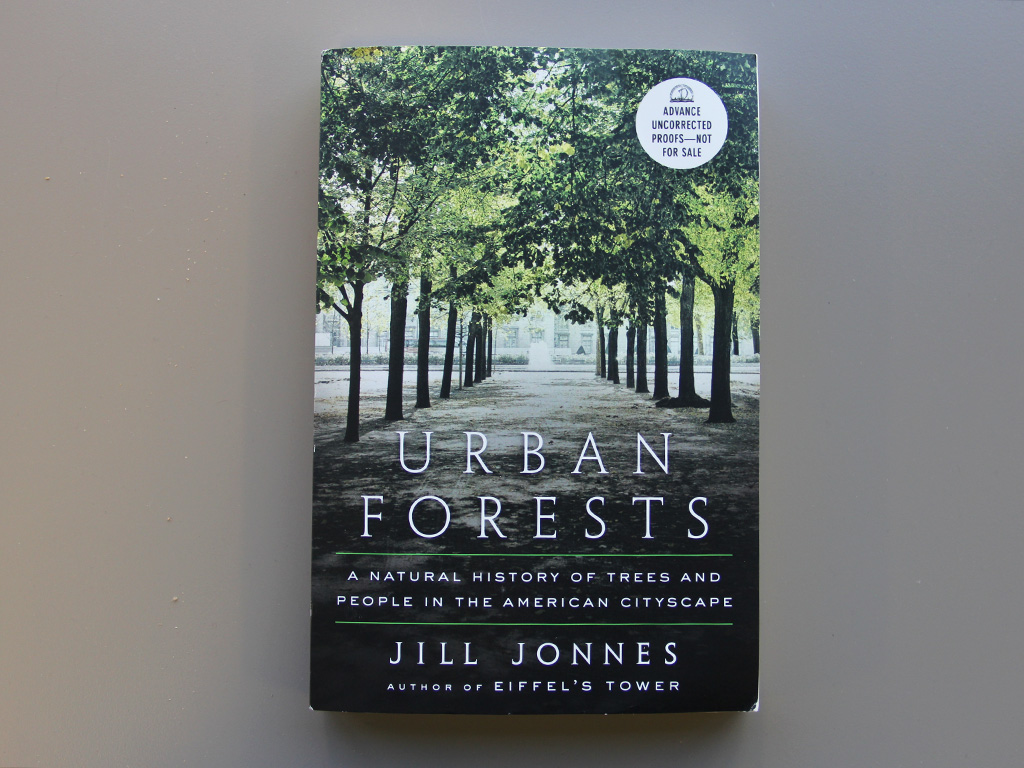

Urban Forests

About This Project

Nature’s largest and longest-lived creations, trees play an extraordinarily important role in our cityscapes, living landmarks that define space, cool the air, soothe our psyches, and connect us to nature and our past. Today, four fifths of Americans live in or near cities, surrounded by millions of trees, urban forests containing hundreds of species. Despite the ubiquity and familiarity of those trees, most of us take them for granted and know little of their specific natural history or civic virtues.

Jill Jonnes’s Urban Forests is a passionate, wide-ranging, and fascinating natural history of the tree in American cities over the course of the past two centuries. Jonnes’s survey ranges from early sponsors for the Urban Tree Movement to the fascinating stories of particular species (including Washington, DC’s famed cherry trees, and the American chestnut and elm, and the diseases that almost destroyed them) to the institution of Arbor Day to the most recent generation of tree evangelists who are identifying the best species to populate our cities’ leafy canopies. The book examines such questions as the character of American urban forests and the effect that tree-rich landscaping might have on commerce, crime, and human well-being. As we wrestle with how to repair the damage we have wrought on nature and how to slow climate change, urban forests offer an obvious, low-tech solution. (In 2006, U.S. Forest Service scientist Greg McPherson and his colleagues calculated that New York City’s 592,000 street trees annually saved $28 million in energy costs through shading and cooling, or $47.63 per tree.)

Chapter One: “So Great a Botanical Curiosity” and “The Celestial Tree”: Introducing the Ginkgo and Ailanthus

On July 7, 1806, the wealthy Philadelphia plant collector William Hamilton, sixty-one, dipped his quill pen into an inkwell and began a postscript to a letter to President Thomas Jefferson, who was summering down at Monticello. “In the autumn, I intend sending you if I live,” wrote Hamilton, then in the throes of searing gout pain, “three kinds of trees which I think you will deem valuable additions to your garden.” Hamilton took competitive pride in possessing every possible botanical rarity. Over the course of twenty-five years, he had transformed the Woodlands, his six-hundred-acre estate overlooking the Schuylkill River, into the young nation’s premier showcase for exotic plants and trees. Jefferson, himself an ardent gardener, had pronounced his friend Hamilton’s country home “the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England.”

On July 7, 1806, the wealthy Philadelphia plant collector William Hamilton, sixty-one, dipped his quill pen into an inkwell and began a postscript to a letter to President Thomas Jefferson, who was summering down at Monticello. “In the autumn, I intend sending you if I live,” wrote Hamilton, then in the throes of searing gout pain, “three kinds of trees which I think you will deem valuable additions to your garden.” Hamilton took competitive pride in possessing every possible botanical rarity. Over the course of twenty-five years, he had transformed the Woodlands, his six-hundred-acre estate overlooking the Schuylkill River, into the young nation’s premier showcase for exotic plants and trees. Jefferson, himself an ardent gardener, had pronounced his friend Hamilton’s country home “the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England.”

Nothing gave Hamilton more joy than showing off his vast greenhouse with its ten thousand plants and his landscaped “natural” pleasure grounds, whose lawns sloped down to the river, artfully “interspersed with artificial groves . . . of trees collected from all parts of the world.” He relished his visitors’ amazement as they stared at strange “foreign trees from China, Italy, and Turkey,” fingering the unusual leaves and bark, inhaling their “balmy odours.” As Massachusetts congressman Manasseh Cutler recalled of a visit to the greenhouse: “Every part was crowded with trees and plants, from the hot climates, and such as I have never seen. All the spices. The Tea plant in full perfection. In short, [Hamilton] assured us, there was not a rare plant in Europe, Asia, Africa, from China and the islands in the South Sea, of which he had any account, which he had not procured.” Another botanical pilgrim to the Woodlands favored with a personal tour peered in pleasure at “the bread-fruit tree, cinnamon, allspice, pepper, mangoes, different sorts, sago, coffee from Bengal, Arabia, and the West-Indies, tea, green and bohea, mahogany, Japan rose, rose apples. . . . The curious person views it with delight, and the naturalist quits it with regret.”

Hamilton, famous as a genial host and a great talker, was not, however, generous with his green prizes. Once during a dinner party, he entered his greenhouse to pick a special camellia for the table’s centerpiece and came upon a young lady with said flower in her hair. Hamilton hurled a curse, exclaiming, “Madam, I had rather have given you one hundred guineas than that you should have plucked that precious blossom.” Philadelphia nurseryman Bernard McMahon complained to Jefferson that while he had bestowed upon Hamilton “a great variety of plants . . . he never offered me one in return. . . . I well know his jealousy of any person’s attempt to vie with him, in a collection of plants.”

Jill Jonnes is the author of Eiffel’s Tower, Conquering Gotham, Empires of Light, and South Bronx Rising. She was named a National Endowment for the Humanities scholar and has received several grants from the Ford Foundation. For more information, please visit: www.jilljonnes.com